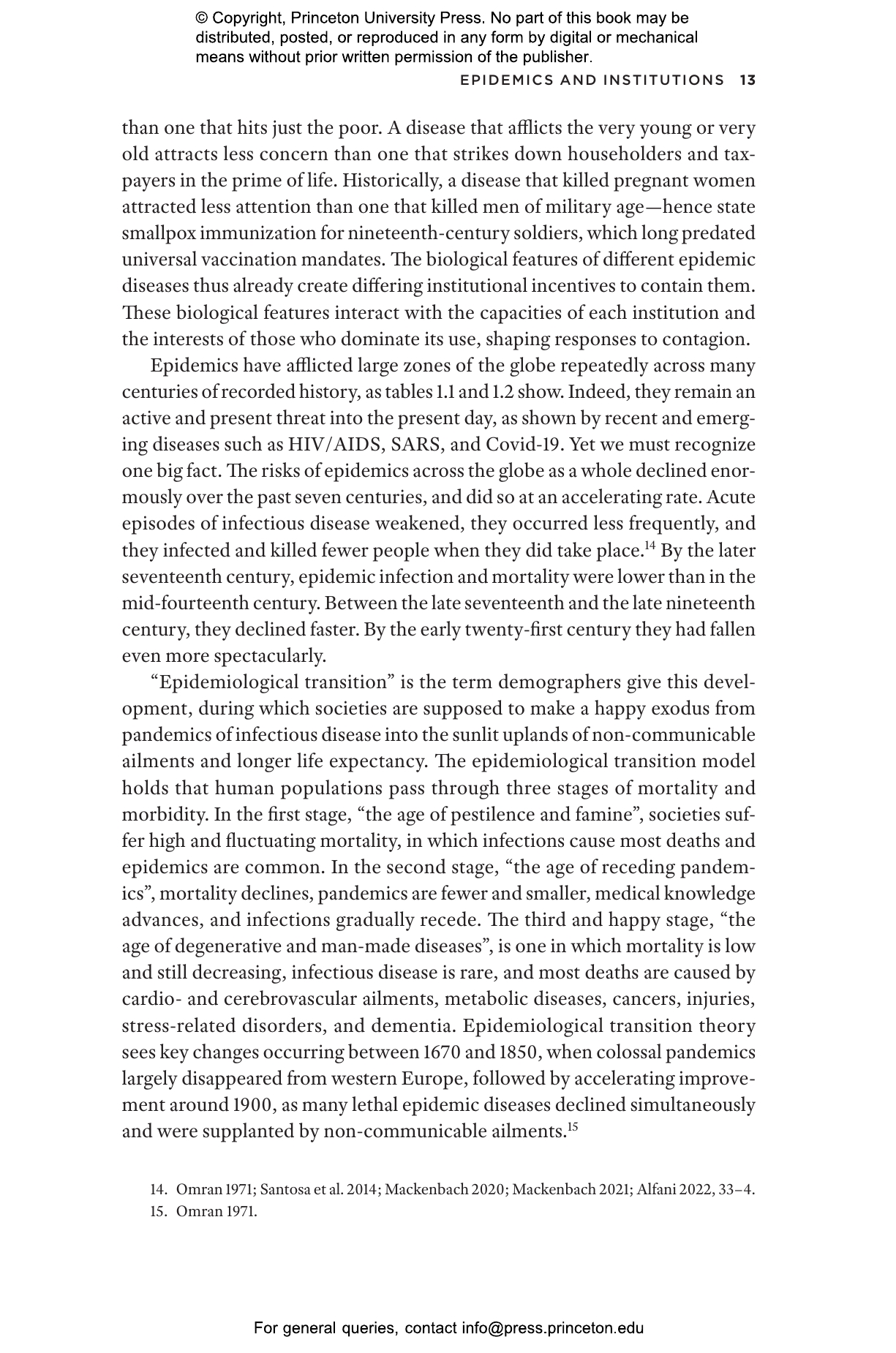

How do societies tackle epidemic disease? In Controlling Contagion, Sheilagh Ogilvie answers this question by exploring seven centuries of pandemics, from the Black Death to Covid-19. For most of history, infectious diseases have killed many more people than famine or war, and in 2019 they still caused one death in four. Today, we deal with epidemics more successfully than our ancestors managed plague, smallpox, cholera or influenza. But we use many of the same approaches. Long before scientific medicine, human societies coordinated and innovated in response to biological shocks—sometimes well, sometimes badly.

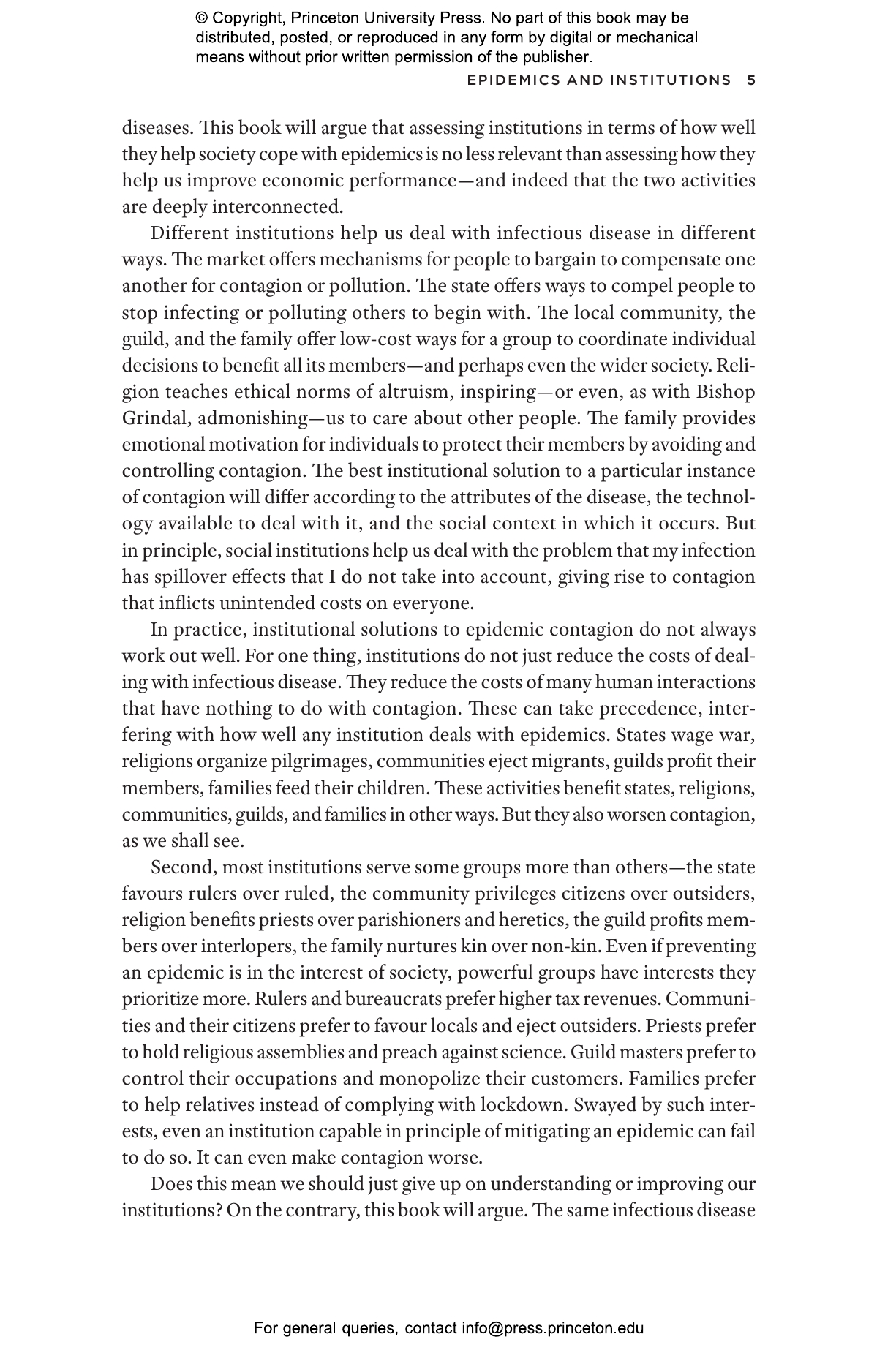

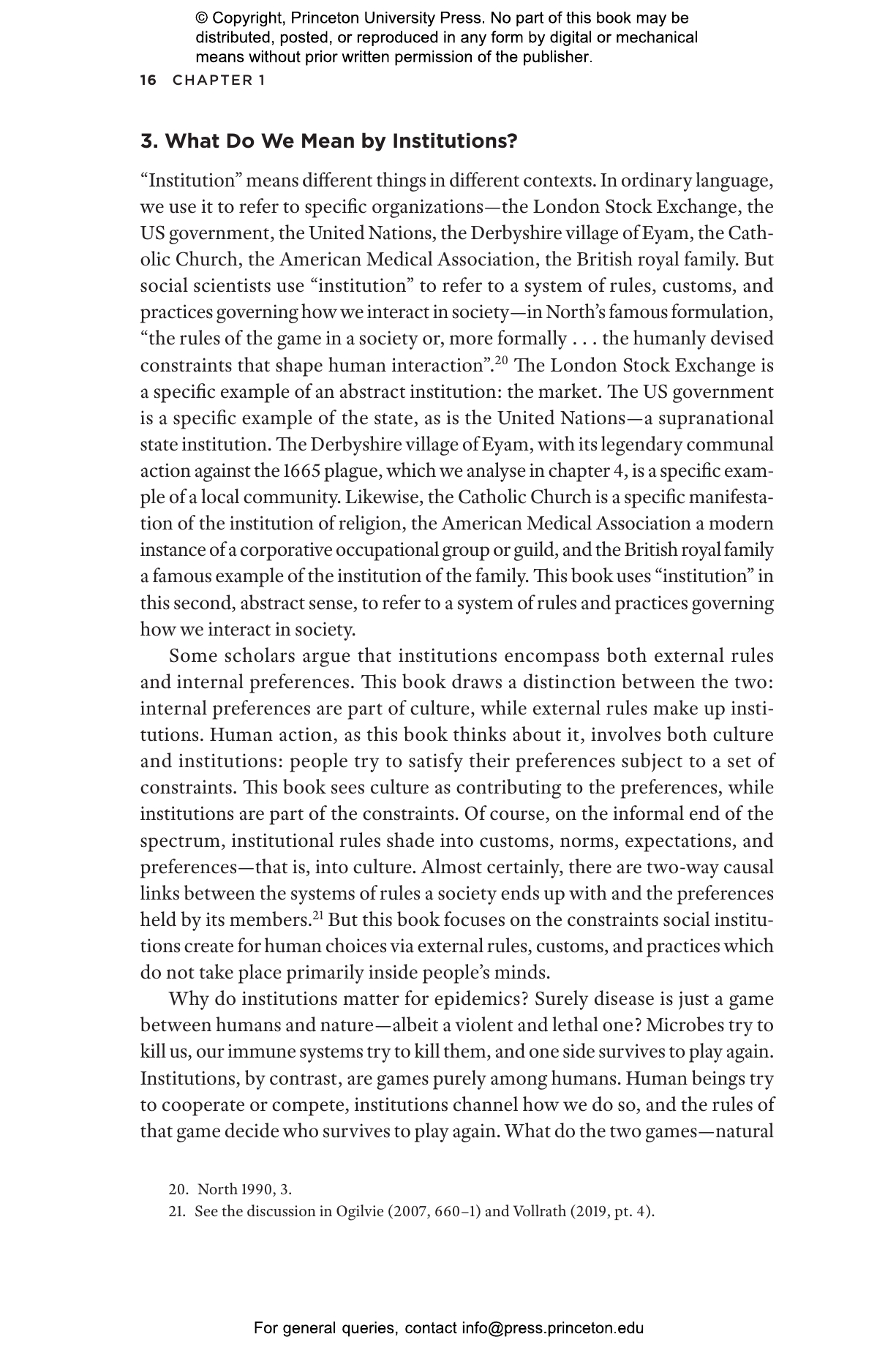

Ogilvie uses historical epidemics to analyse how human societies deal with “externalities”—situations where my action creates costs or benefits for others beyond those that I myself incur. Social institutions—markets, states, communities, religions, guilds, and families—help us manage the negative externalities of contagion and the positive externalities of social distancing, sanitation, and immunization. Ogilvie shows how each institution enables us to coordinate, innovate and inspire each other to limit contagion. But each institution also has weaknesses that can make things worse. Markets shut down voluntarily during every epidemic in history—but they also brought people together, spreading contagion. States mandated quarantines, sanitation, and immunization—but they also waged war and censored information, exacerbating epidemics. Religions admonished us to avoid infecting our neighbours—but they also preached against science and medical innovations. What decided the outcome, Ogilvie argues, was a temperate state, an adaptable market, and a strong civil society where a diversity of institutions played to their own strengths and checked each other’s flaws.

Sheilagh Ogilvie is the Chichele Professor of Economic History at the University of Oxford, a fellow of All Souls College, and director of the Oxford Centre for Economic and Social History. She is the author of The European Guilds: An Economic Analysis (Princeton), Institutions and European Trade: Merchant Guilds, 1000–1800, A Bitter Living: Women, Markets, and Social Capital in Early Modern Germany, and State Corporatism and Proto-Industry: the Württemberg Black Forest, 1580–1797.

“There is no other book that that systematically works through the inherent institutional challenges (externalities, information failures, asymmetric risk) of epidemic disease with this kind of historical richness. This is an important and stimulating contribution.”—Kyle Harper, University of Oklahoma

“Scholars will come to consider this book an essential reference, due to the specific angle from which it looks at epidemics and pandemics—there simply isn’t anything similar on the market. The author makes full use of her own expertise, which is truly impressive in many areas, including the general history of preindustrial Europe and the history of institutions.”—Guido Alfani, Bocconi University

“This superb book investigates some of the greatest crises that human societies have faced, in the form of major epidemics from the Black Death to Covid-19. What emerges vividly is the dismaying mixture of selfishness and ignorance repeatedly displayed by the elites, notably by rulers at every level, clerics, and doctors. This is history that could hardly be more relevant, a powerful cautionary tale explored with great analytical skill.”—Robin Briggs, University of Oxford

“Combining wide-ranging in-depth analysis with rigour and lucidity, this book transforms our understanding of how epidemics have been dealt with in history. Everyone interested in how societies deal with disease and in their resilience, in the past and in the present, will have to read this book.”—Chris Wickham, author of The Inheritance of Rome: A History of Europe from 400 to 1000

“In this impressive work, Ogilvie draws on a wealth of historical evidence and judicious reasoning to explore the ways institutions have interacted and continued to interact with pandemics. Some cherished institutions tend to make disease transmission easier, while others could control the spread of disease long before modern science attacked the microorganisms that caused pandemics. Controlling Contagion succeeds admirably as a compact history of pandemics as well as a thoughtful discussion of the implications of the way we respond to these events.”—Timothy Guinnane, Yale University

“Sheilagh Ogilvie deploys concepts derived from economic theory to enrich our understanding of historical epidemiology. Her analysis will be of great value to the specialist and general reader alike.”—John Landers, author of The Field and the Forge:Population, Production, and Power in the Pre-Industrial West

“This remarkable and wide-ranging book is essential reading for anybody interested in the history of epidemic disease from plague to COVID.”—John Henderson, author of Florence under Siege: Surviving Plague in an Early Modern City

“A stunning book in scope and method. To examine how human societies have dealt with epidemics over seven centuries, Ogilvie blends a rigorous social scientific approach with unusual sensitivity to local specificities and power structures. Her nondeterministic institutional analysis has broad implications for how we think about both the past and the present.”—Francesca Trivellato, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton University

"With this exciting new study of epidemic disease, Sheilagh Ogilvie makes another persuasive case for institutions as significant determinants of economic, social and demographic outcomes. This wide-ranging research offers new perspectives on the past and valuable lessons for future epidemiological challenges."—Tracy Dennison, California Institute of Technology