I live less than a mile from Walden Pond. There, in the woods on the east side of the pond, Thoreau built his small cabin and wrote his great book. It is probably true that Thoreau left his cabin from time to time to walk into the town of Concord, one mile away, to see his family and others. But for the vast majority of the two years, he remained in that cabin alone, thinking, writing, and simply experiencing life.

Some days, but not often enough, I manage to pry myself loose from the rush and heave of the world and take a quiet walk around the pond. In the winter, the air is crisp and sharp; in the summer soft and aromatic. In winter, I am usually the only one on the trail. The woods stand stiffly, silent and white, and the pond is sometimes frozen over. All I can hear is the crunching of my boots in the snow. In the spring, ducks swim in the pond. I listen to the calls of the blackbirds and chickadees and kingfishers and red-tailed hawks. “Our life is frittered away by detail,” wrote Thoreau. “Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity. I say, let your affairs be as two or three, and not a hundred or a thousand.”[i] I want to recover what I have lost, what all of us have lost. I want to live with simplicity. I want to live in the slow world.

Not long ago, I was sitting at my desk at home and suddenly had the horrifying realization that I no longer waste time. It was one of those rare moments when the mind is able to slip out of itself, to gaze down on its convoluted gray mass from above, and to see what it is actually doing. And what I discovered in that flicker of heightened awareness was this: from the instant I open my eyes in the morning until I turn out the lights at night, I am at work on some project. For any available quantity of time during the day, I find a project; indeed I feel compelled to find a project. If I have hours, I can work on an article or book. If I have a few minutes, I can answer an email. With only seconds, I can check telephone and text messages. Unconsciously, without thinking about it, I have subdivided my waking day into smaller and smaller units of “efficient” time use, until there is no fat left on the bone, no breathing spaces remaining. I rarely goof off. I rarely follow a path that I think might lead to a dead end. I rarely imagine and dream beyond the four walls of a prescribed project. I hardly ever give my mind permission to take a recess, go outdoors and play. What have I become? A robot? A cog in a wheel? A unit of efficiency myself?

I can remember a time when I did not live in this way. I can remember those days of my childhood in Tennessee when I would slowly walk home from school by myself and take long detours through the woods. With the silence broken only by the calls of birds, I would follow turtles as they slowly lumbered down a dirt path. Where were they going, and why? I would build play forts out of fallen trees. I would sit on the banks of my own pond, Cornfield Pond, and waste hours watching tadpoles in the shallows or the sway of water grasses in the wind. My mind meandered. I thought about what I wanted for dinner that night, whether God was a man or a woman, whether tadpoles knew they were destined to become frogs, what it would feel like to be dead, what I wanted to be when I became a man, the fresh bruise on my knee. When the light began fading, I wandered home.

I ask myself: What happened to those slow, simple hours at the pond? How has the world changed? Of course, part of the answer is that I grew up. Adulthood undeniably brings responsibilities and career pressures and a certain awareness of the weight of life. Yet that is only part of what’s happened. Indeed, an enormous transformation has occurred in the world from the 1950s and 1960s of my youth to the twenty-first century of today. A transformation so vast that it has altered all that we say and do and think, yet often in ways so subtle and pervasive that we are hardly aware of them. Among other things, the world today is faster, more scheduled, more fragmented, less patient, louder, more wired, more public. For want of a better word, I will call this world the “wired world.” By this term, I do not mean only digital communication, the internet, and social media. I also mean the frenzied pace and noise of the world.

There are many different aspects of today’s time-driven, wired existence, but they are connected. All can be traced to recent technological advances and economic prosperity in a complex web of cause and effect. Throughout history, the pace of life has always been fueled by the speed of communication. The speed of communication, in turn, has been central to the technological advance that has led to the internet, social media, and the vast and all-consuming network of the grid. That same technology has also been part of the general economic progress that has increased productivity in the workplace, which, when coupled with the time-equals-money equation, has led to a heightened awareness of the commercial and goal-oriented uses of time—at the expense of the more reflective, free-floating, and non-goal-oriented uses of time.

These changes actually began picking up steam with the Industrial Revolution. Thoreau was well aware of them. In Thoreau’s day the new communication technologies were the telegraph and the railroad. “We do not ride on the railroad,” wrote Thoreau; “it rides on us.”[ii] When the telegraph was invented in the nineteenth century, information could be transmitted at the rate of about 3 bits per second. By 1985, near the beginnings of the public internet, the rate was about 1,000 bits per second. Today, the rate is about 1,000,000,000 bits per second. A friend of mine who has been practicing law for thirty years wrote to me that her “mental capacity to receive, synthesize, and thoughtfully complete a legal document has been outpaced by technology.” She says that with the advent of email, her clients want immediate turnaround, even on complex matters, and the practice of law has been “forever changed from a reasoning profession to a marathon.” A momentous but little discussed study by the University of Hertfordshire in collaboration with the British Council found that the walking speed of pedestrians in thirty-four cities around the world increased by 10 percent just in the ten-year period from 1995 to 2005.[iii] All driven by the speed of communication and commerce, driven, in turn, by new technology.

Technology, however, is only a tool. Human hands work the tool. Behind the technology, I believe that our entire way of thinking has changed, our way of being in the world, our social and psychological ethos. Many of us cannot spend an hour of unscheduled time, cannot sit alone in a room for ten minutes without external stimulation, cannot take a walk in the woods without a smartphone. These behavioral syndromes are part of the noisy, hyperconnected, splintered, and high-speed matrix of the wired world. Henry David said that our affairs should be two or three, not a hundred or a thousand. We Americans now send six billion text messages a day and, on average, check our phones for those messages every ten minutes.

What exactly have we lost? If we are so crushed by our schedules and to-do lists and hyperconnected media that we no longer have moments to think and reflect on ourselves and the world, what have we lost? If we cannot sit alone in a quiet room with only our thoughts for ten minutes, what have we lost? If we no longer have time to let our minds wander and roam without particular purpose, what have we lost? If we and our children no longer have time to play? If we no longer experience the quality of slowness, or a digestible rate of information, or silence, or privacy? More narrowly, what have I personally lost when I must be engaged with a project every hour of the day, when I rarely let my mind spin freely without friction or deadlines, when I rarely sever myself from the rush and the heave of the external world—what have I lost?

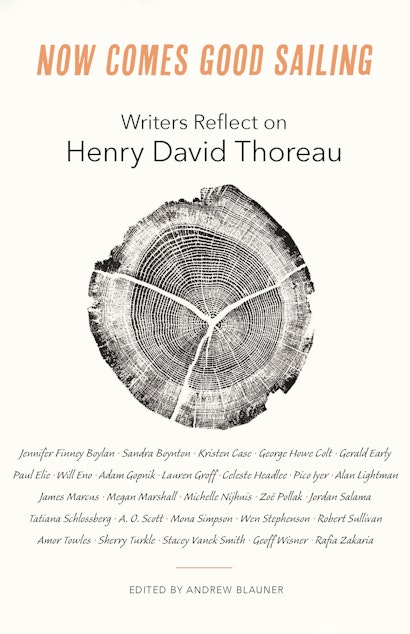

This essay is an excerpt from the chapter “To a Slower Life” by Alan P. Lightman in the book Now Comes Good Sailing: Writers Reflect on Henry David Thoreau, edited by Andrew Blauner.

Alan P. Lightman is professor of the practice of the humanities at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His books include Screening Room and Einstein’s Dreams.

Notes

[i] Henry David Thoreau, Walden (New York: W. W. Norton, 1951), 106.

[ii] Ibid., 108.

[iii] British Council press release, http://www.richardwiseman.com/resources/Pace%20of%20LifePR.pdf.