This essay was translated by Kate Deimling.

Every time I start working on a book I’ve been dreaming about, I’m amazed that no one has already written it. Then, after a few months of increasingly painstaking research, I realize: Of course, this is why!

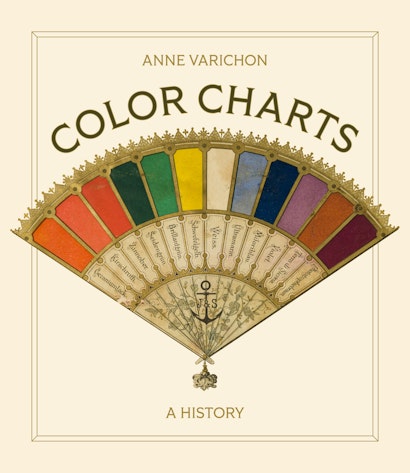

All research is a long adventure, strewn with pitfalls and hemmed in by constraints. As I researched Color Charts: A History, three major challenges arose.

First of all, this field of research has been ignored—or even denigrated—by the social sciences for decades. Color was at best a non-topic. With only a handful of publications devoted to it until recently, there was still a great deal of ground to be cleared. After all, color doesn’t satisfy hunger, it doesn’t warm you up, it doesn’t enable you to climb a wall or even defend yourself. It’s an accessory, a superfluous quality. What’s more, in the West, color has long suffered from an ambiguous status, somewhere between mistrust and fascination. Like the English word conceal, color traces its etymology to Latin celare, “to hide.” Color is suspect because it conceals the nature or truth of things.

Secondly, exploring color sampling means questioning fragments. You can’t do anything with these little bits and pieces, and, taken out of context, they can’t say much. They look like trivial, mute, useless traces.

Finally, many color samples come from the work of craftspeople or tradespeople. These activities required great intelligence and skill, but past generations often overlooked or dismissed them. So much of their material history has been neglected, if not simply destroyed. Few institutions or collectors have preserved it.

This is why researching color sampling meant reconstructing entire worlds from scraps of fabric or daubs of paint.

Yet the anthropology of color is an incredibly rich field. Color has been with humanity since its earliest beginnings. As a clue to the environment (think of ripe fruit or threatening weather), color helps us decipher the world around us. It is also an outward sign for people and communities (in clothing, for example). It can define a culture in the eyes of others. Without a word, color speaks volumes: He’s dressed in red because he was born the son of the chief or I’m wearing yellow, I come from far away, I’m a foreigner. Finally—and perhaps most importantly—color is a source of emotions that can be profound, overwhelming, and sustaining.

Since the dawn of time, humans have longed for color. It has given rise to an extremely sophisticated body of knowledge about the resources offered by nature. It has led to the development of skills ranging from the simplest to the most refined. Women have clearly played a central role. Women’s knowledge of color has been handed down over the centuries, often orally, expressing attention, determination, obstinacy, resistance, intelligence, and courage.

Through my research, I have deciphered color charts to reveal their historical, linguistic, aesthetic, and anthropological treasures. Carefully cut fabric, leather, paper, or rubber; strips of wood or linoleum; delicate skeins of silk; carefully placed circles of pigment, paint, or pastel; meticulous reproductions of the hues of urine, lipstick, or iris petals. Each color chart is its own world. At the same time, it brings back to life an individual and collective history, catalyzing scientific, technical, and artistic knowledge. Color charts are also interfaces. They have led to crucial changes in the way we think about color. Finally, they are physical traces of color as embodied in matter. They reconstruct an approach to color where the beauty of the shade was inseparable from its concrete presence in a medium.

That world is gone. The history of color sampling is also a requiem. Synthetic chemistry combined with industrial processes and globalization have all but wiped out the old, diverse, full, fleshy, juicy conceptions of color. But this requiem also brings hope, because reviving this vanished splendor may help create the conditions for its re-emergence and reinvention.

The color chart demands absolute rigor in the rendering of colors. At the same time, it becomes an aesthetic object, opening up the immensity of the imagination. Few tools offer such a vast and fertile space to explore, to think, to dream, and to feel.

Anne Varichon is an anthropologist specializing in material cultures and ideas about color. She is the author of Colors: What They Mean and How to Make Them.