A few years ago, I was in the Medieval Collection of the Metropolitan Museum in New York City examining one of the objects I was writing a book about when a father came by with two children, a boy of about 10 and a girl of 7 or 8. He was taking them to see the medieval armor in the next exhibit room. “Excuse me,” I said to the little girl, “Would you like to see something?” And I showed her the so-called beguine cradle I was studying: a miniature bed, elegantly carved, adorned with bells, and furnished with a velvet coverlid beautifully embroidered with gold thread and seed pearls. Not only the daughter but also the father and son were enchanted when I showed them how the little bed was made with arched windows in the side and had spires at the four corners like the roof of a church, on top of which perched angels playing musical instruments. We walked around it seeing how it seemed alternatively bed and building as our perspective changed. Even though, as it turned out, the child was not a Christian, she had seen Christmas manger scenes lighted up on the lawns of churches and of her neighbors’ houses in suburbia and realized immediately that this little bed might be placed in a church at Christmas, echoing the larger church in which it was situated.

The family then adopted me as tour guide, and we went on together to see the armor on the big model horses in the next room. I think the children paid attention to what those embroidered and embossed trappings of fighting said not just about war but also about athletic prowess and the problematic nature of violence in part because we had already talked about how an object can be several different things at once. After all, we asked, why make such beautiful objects simply to help men and horses kill each other? That elaborate armor must mean something more complex.

I am writing a book about religious objects such as the beguine cradle in order to demonstrate how objects themselves act on viewers to impel them to see in complicated ways. For example, I argue that the crowns worn by medieval nuns conveyed by their very shape (with bands that pointed up and down) both the heavenly status the woman hoped to gain in the afterlife and the impermanent, transitory state she occupied on earth in her life of prayer. Similarly, images of Christ’s footprints, depicted in devotional books and brought home from the Holy Land in simple cut-outs, conveyed a sense of Christ’s presence and absence on earth. Pilgrims and crusaders believed they carried power itself when they brought home measures of the supposed footprints of the departed Christ from the Mount of Olives.

Historians of the Middle Ages, even art historians, have tended to assume that we should read the works of theologians, devotional writers, and poets to find out what images meant. Medieval philosophers in the universities, learned monks and nuns in their convents, wrote much about abstruse topics such as “negative theology” or “the names of God” that elaborated complex ideas about how language and mental concepts might refer to the ineffability of a Divine beyond all naming. I argue that, if we look with care, as I tried to help the father and his two children to do in the Metropolitan Museum, medieval art itself tells us much about how to look and feel and know. After all, most medieval people did not read theologians and philosophers nor did they fully understand the Latin liturgy they heard. But they used the devotional images in chapels, churches, even in their own bedrooms, to reach beyond their daily lives toward complex, paradoxical, and liberating meaning. They thought with objects, and objects taught them how to think. A medieval person might, for example, move around in a single prayer card, such as this depiction of Christ’s suffering, to contemplate the common human experiences of grief, loss, responsibility for evil, and redeeming love.

We can never in any simple way recapture medieval experience. It would be arrogant as well as false to try. Moreover, in the sometimes sterile atmosphere of a museum where objects may be crowded into a room and yet isolated under glass, it can be hard to see them. We need to walk around them, consider their size and craftsmanship, to imagine what it would be like to handle them or to lift them up amidst prayer and incense or in the smoke of battle. If we do this, we can frequently learn more from looking than from reading the museum labels that usually provide indications only of date and provenance. I argue that it is the job of historians and art historians of the distant past to help viewers learn to see, but fortunately, if we are thoughtful, honest, and careful, we will understand that the objects themselves often do that teaching for us.

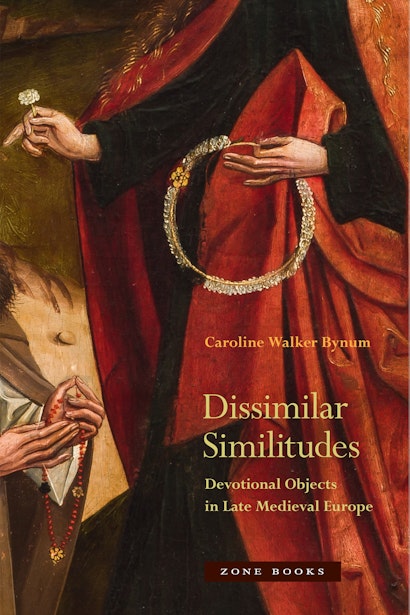

Caroline Walker Bynum is Professor emerita of Medieval European History at the Institute for Advanced Study, and University Professor emerita at Columbia University in the City of New York. She studies the religious ideas and practices of the European Middle Ages from late antiquity to the sixteenth century. In the 1980s, she worked on women’s spirituality in Europe; in the 1990s, she turned to the history of the body. Her recent work, Wonderful Blood (2007) and Christian Materiality (2011), locates the upsurge of new forms of art and devotion in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries against the background of changes in natural philosophy and theology and reinterprets the nature of Christianity on the eve of the reformations of the sixteenth century. Her essays “In Praise of Fragments” (in Fragmentation and Redemption), “Why All the Fuss av������ the Body?” (in Critical Inquiry and reprinted in The Resurrection of the Body, expanded edition, 2017), and “Wonder” (in Metamorphosis and Identity) are widely cited as discussions of historical method. Bynum has taught at Harvard, the University of Washington in Seattle, and Columbia University. She was a MacArthur Fellow from 1986 to 1991 and has won the Ralph Waldo Emerson Prize of Phi Beta Kappa, the Jacques Barzun Prize of the American Philosophical Society, the Gründler Prize in Medieval Studies, and the Haskins Medal of the Medieval Academy of America. She has won three undergraduate teaching awards, one from the University of Washington and two from Columbia University. She is a past president of the Medieval Academy of America and the American Historical Association, a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Philosophical Society, and the Orden Pour le Mérite für Wissenschaften und Künste of the Federal Republic of Germany, and a Fellow of the Medieval Academy of America and the British Academy.