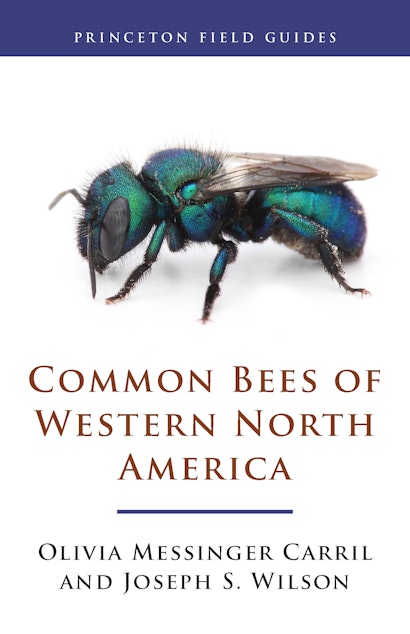

The temperature is climbing, and the great outdoors is teeming again with flowers, insects, birds, and other creatures of all shapes and sizes. To celebrate the arrival of summer and the gifts of nature that come with it, we asked several of our naturalist writers and scholars to respond to the following question: How did you fall in love with natural history? This week, we hear from Dr. Olivia Messinger Carril, lifelong admirer of bees and co-author of Common Bees of Western North America.

I am a biologist who has spent her career chasing wild bees across the vast western landscapes of the United States. My goal is to expand our understanding of who lives where and why. I love my job. I love that I am doing my best work when I am staring at some stunning flower, often one in a field of hundreds, in an area seldom seen by other humans. I love the sound of a bee teasing open the petals of a flower. I love that my job allows me to bring my young daughters with me and show them the wonders of being outside. I love that I get to camp and see a universe of stars most nights of the summer. I even love being hot, developing a crust of salt on my skin and drinking overly warm water that has sat in the sun.

I agree with the Teddy Roosevelt who wrote the following:

“�ĦI can no more explain why I like ‘natural history’ than why I like California canned peaches….”

Where Mr. Roosevelt and I disagree is the rest of that statement:

“�Ħnor why I do not care for that enormous brand of natural history which deals with invertebrates any more than why I do not care for brandied peaches.”

Clearly, he never tried his hand at studying wild bees.

I can’t put my finger on the moment that determined I would choose to study ecology for the rest of my life, but I do know that I was fortunate to be raised in a family where the door to nature was always open, and whether I liked it or not, my parents booted me through it at every opportunity. By the time I reached college, that door had been subtly closed behind me. It was “natural” to be outside.

My first memory is the sound of my sleeping bag swishing and rustling as I tossed on my sleeping mat and my mother admonishing me in the hoarse nighttime voice of an exhausted parent: “Go. To. Sleep.” When I was three, my father was a logger in eastern Oregon, and his young wife and daughter (me) spent the summers camping with him among Ponderosa Pines and Elk Sedge. I spent my summers half-clothed and filthy; my mother taught me how to pick ripe huckleberries and how to soak yourself in a six-inch-deep creek. And the “ew” factor of being in the great outdoors was never a problem I had to overcome.

Later, when my father went back to school for electrical engineering and we moved to Utah, we spent our weekends in the deserts west of Salt Lake City, chasing pronghorn and spying on golden eagles. My parents bought me a plant press and binoculars and put me in charge of a family “journal” documenting all that happened on any given outing. These outings awoke the mystery-lover in me. I felt like Sherlock Holmes, reading clues left behind by the animals who lived out there; in order to understand what happened when I wasn’t around, I had to find the evidence. Old birds’ nests told me who had lived there before. Bones did too, but they also told me who ate who. Animal scat marked who had passed through camp the night before. And blooming flowers spoke of pollinators that I didn’t see. There was a truth out there; it was my job to discover it.

My plan upon leaving high school was to become a pilot. I loved flying and thought that such a career would give me the opportunity to see the world. At the last minute, I switched universities and chose biology as my major. I can’t say why. Did it feel safer? More exciting? Or was I not ready to give up searching for clues? Regardless of the reason, the outcome is one I don’t regret. I was fortunate to find mentors at Utah State University that gave me opportunities to try fieldwork, “work” that was so enjoyable it hardly seemed right to get a paycheck. I helped with botany surveys, assisted with Pronghorn Antelope tagging, tagged along on bird censuses, and, finally, took on a bee survey of Pinnacles National Monument in California.

My first year in Pinnacles, I camped for three months straight, hiking the monument with a net every day to sample bees on the many plants in this diverse ecosystem. I kept a journal and wrote all the questions that came to my mind as I worked (there were many). I loved my growing collection in the same way someone else might love their baseball cards. I appreciated that what I was learning while I “worked” might help a land manager protect these bees in the long run. I was completely hooked.

Studying bees allows me to sustain my childhood enthusiasm for nature, for mystery, and for exploration. Every time I sample for bees, I gather new clues and reveal new facets of cryptic species interactions. I love being hot and dusty, but more than that I love that studying bees, for me, is a tangible manifestation of all the ecological concepts I studied in school. At my feet, on a regular basis, I can watch “ecosystem function” actually happen! I can see competition, resource limitation, herbivory, and fitness. Predation becomes real. Pollinator networks are actual entities. And ecology becomes nuanced, intricate, and just complicated enough to avoid complete understanding, all while maintaining a stunning wild beauty.

“The pursuit of truth and beauty is a sphere of activity in which we are permitted to remain children all our lives.”—Albert Einstein

Olivia Messinger Carril is an independent scholar who has been studying bees for more than two decades.