A few years ago, after I had just met my boyfriend, we found ourselves driving in circles around a Colorado carpark. He claims the carpark was confusingly oriented, that its architecture seemed to indicate that we would go either up or down if we kept going. I contend, still, that we were in the middle of such a good conversation that he didn’t want to interrupt it by parking, by getting snagged on a new train of thought, and so that’s why, for twenty or thirty or even forty minutes, he circled slowly as we talked. What we were talking about was the partnership between writer (and strategist, as I argue) Aline Louchheim Saarinen and her husband, employer, and essential creative collaborator, the midcentury Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen. What we were actually talking about was whether we could collaborate in the way that Aline and Eero had.

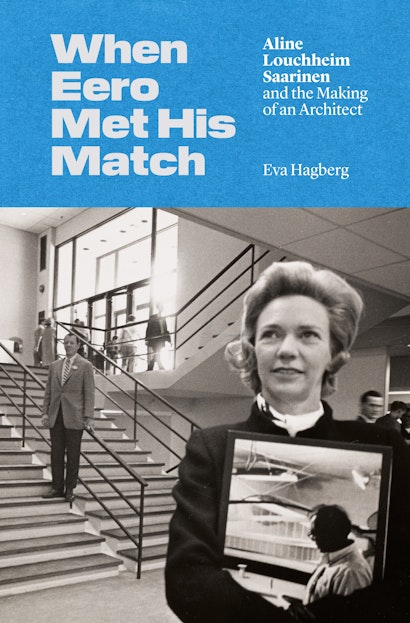

Briefly: Saarinen designed the TWA Terminal at JFK Airport that looks like a soaring bird (an analogy Louchheim was instrumental in pushing), the “Yale Whale” skating rink with its ridged curve of a roof, and the St. Louis Arch. He was influenced by his father, Eliel Saarinen, and was part of a whole Cranbrook crowd. His offices were in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, until the firm was supposed to move to New Haven, but he died suddenly at fifty-one in 1961 before he had the chance to come east. Briefly: Louchheim was a product of Vassar, an art critic at the New York Times, a socially gifted connector who encountered Saarinen because of a story she wrote about him in 1953 for the New York Times (which she scandalously allowed him to edit before it ran). She was influenced by the people she surrounded herself with—the magazine editor Douglas Haskell, the first full-time architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable (who suggested that Louchheim was surely more popular given that “gentlemen prefer blondes”), and the playwright Clifford Odets. While reporting her profile, she fell in love with Saarinen and left her life in New York in order to sit across from him in his Bloomfield Hills office, where she chewed on pencils and made him famous.

We were talking about Aline and Eero because we were really trying to talk about ourselves, and nothing lessens the potential strain on a new relationship like comparing it to someone else’s. We had begun to realize that we might be compatible coworkers, this boyfriend and I. He is an industrial and furniture designer, skilled beyond belief, who’d made a name for himself with work that is at once historically influenced and profoundly contemporary, with pieces that spark a moment of delight, of curiosity, of disorientation and reorientation. He was doing handmade work when everyone else was doing mass produced; mass production when everyone else was doing handmade. He’d gone to RISD and worked with all the major designers, none of whom I can name, but all of whom you’ve heard of. Meanwhile, I was working in public relations, focusing on getting architects published, my tactics and strategy guided in part by how Aline had done it for Eero. I hadn’t been involved with any of my clients, though. So we’d have to figure that part out.

“What if we worked together,” one of us floated. “Just like Aline worked with Eero.” We wanted to, but I was nervous. I’d seen how their interactions had changed from their earliest letters, in which Eero told Aline his drives, his goals—like becoming Dean at Yale—and in which Aline encouraged, molded, shaped his approaches, to their latest office memoranda, passed back and forth through the office. One memorable letter had scrawled, in Eero’s blocky text, “Should you not answer this yourself?” Aline’s response was that she did not have a crystal ball. I could see the difference just a few years—between courtship and marriage and co-working—could make, and I didn’t want that for myself. And yet, I saw so many possibilities if we could just find a way to join forces.

Are you curious about my designer boyfriend? Are you wondering who he is, and if you have one of his pieces? If so, that’s the point. I want you to be curious. I want you to think about him, to wonder if maybe you too want to feel a moment of delight, of curiosity. I do PR for a living after all, and I learned from the best—from hundreds of office letters and documents that Aline sent to editors, pitching Eero as an architect, as a profile subject. Aline was both subtle and overt in her boosting of Eero; she mentioned him to her powerful and commissioning friends, name dropping whenever she could. And she played a role as eager information provider, as helpful wife. In the 1950s, I believe, she needed that cover in order to professionalize her role, because the role—architectural publicist—hadn’t yet been professionalized. She wove together the personal and the professional in a way that so many of us continue to do today. It was a gift and a sacrifice.

My boyfriend wanted to know where the sacrifices had been, where things had gone sideways. I remembered a letter Aline had written to someone, towards the end of Eero’s life, though of course they didn’t know that yet. She wanted to, she wrote, “confine” (an odd word for an expansive choice, but one that, I believe, spoke to the strength of her desires) her work to interests outside of the office, she said, turning down an invitation to write a book about him. (After he died, she wrote it anyway.) It seemed that she missed her career as an art critic and regretted, perhaps, having gone so far into Eero-world. “That was the trick, then,” I said. That I could always, if I needed to, confine my work to interests outside of my boyfriend’s studio, his business. And so we agreed. We would try it out. And we would see how it went.

Maybe it’s odd to be guided by history more than someone living. But what I learned, over ten years of researching Aline, is just how messy, personal, impromptu, and creative the ways people organized themselves were—and remain. It’s tempting, as a historian, to neaten the motives of others while allowing tremendous flexibility for ourselves. But her motives weren’t neat; mine aren’t neat. I want to sell books, and I want to sell you a Paul Loebach for Roll & Hill Halo chandelier. Contact me for pricing.

Eva Hagberg teaches in the Language and Thinking Program at Bard College and at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation at Columbia University. Her books include How to Be Loved: A Memoir of Lifesaving Friendship and Nature Framed: At Home in the Landscape. She lives in Brooklyn.