Sunday, 5 p.m., Miami

It was 5 p.m. when I woke up in the guesthouse of a villa on Miami’s Star Island, mosquito-bitten and sweaty in the afternoon heat. Since coming to Miami three days earlier to follow Santos, a twenty-six-year-old club promoter, to Ultra, the renowned electronic dance music festival, I had experienced a whirlwind of party hopping, from club to club to hotel penthouse to P. Diddy’s early morning pool party; finally, Santos, having run out of after-parties on day four, wired up the speakers to keep the party going at our villa. The booming electronic music finally stopped around noon, or at least that’s when I fell asleep.

This isn’t really our villa; it’s a rental priced at $50,000 for the weekend, and this weekend, it was home to a group of young men flush with cash from their jobs at a Southern California mortgage bank. The rental agent had invited Santos and “his girls,” models mostly, to stay in the bankers’ villa for the weekend of parties. The bankers were excited at the prospect of a bunch of models sleeping in the attached guesthouse. Models were such a fixture in the global VIP club scene that the phrase “models and bottles” came to denote a good time. As an “image promoter,” Santos’s job mostly involved ferrying models to and from exclusive parties well into the night, and even, I was learning, into the next day.

In my muggy little guest room, I gingerly stepped between two twin beds, maneuvering through dresses, high heels, and the other spilled contents of suitcases, to rummage in my Chanel handbag for a cold McDonald’s breakfast burrito purchased in a hurry hours ago, between parties, then carried it and my laptop outside to sit by the pool. No sign of the bankers, nor of Santos and his models, only empty beer and champagne bottles scattered around the manicured lawn and palm trees.

It was quiet except for the ringing in my ears that always happened after a long night out. It rarely works to shout a conversation over club music. To hear someone in the thick of a 72,000-watt sound system, you have to press a finger against the pointy cartilage part of your near ear, which, when flattened, drowns out background noise and focuses a stream of vocal vibrations straight into your brain.

This is how I understood Santos when, over the noise at the peak of the previous night’s best moments, as crates of champagne were delivered to our table amid cheers and sparklers, he leaned in close to my face, pressed a finger against my ear, and said, “It’s amazing! See, I told you. I’m at the best parties in the world!”

Going out with Santos did indeed offer amazing experiences at extravagant parties packed with beautiful models whose bodies were lit up by the fireworks affixed to the trains of expensive champagne bottles coming our way. At one point the previous night, after a rich man ordered a sparkler-lit procession of dozens of bottles to our table, we each got to drink from our own personal bottle of Dom PĂ©rignon. In place of glasses, our high-heeled shoes littered the tables, so we could dance barefoot on top of the sofas. It was an electric couple of hours shared among Santos, myself, and a dozen other girls and promoters, all part of an exclusive world of beauty and money, both present in excess and on full display.

I had come to Miami in 2012 during the peak party season, in March. By that point, the US economy had recovered from the crash of 2008 but unevenly so, with the most gains going to the least-affected share of top income earners. For the rich, it seemed, the champagne flowed freely throughout the Great Recession. So I joined the party circuit for the world’s “Very Important People” to understand what they do with their huge and growing pools of disposable income, and how they think about wastefully destroying their money—a phenomenon that, to outsiders, often seems ridiculous and disgusting. From 2011 to 2013, I documented a ritualized form of wealth destruction in the elite club scene, one that repeats around the world, from the Hamptons to Saint-Tropez, but one that does not come easy. It takes an incredible amount of labor to enable conspicuous leisure, and this labor upholds a gendered economy of value in which women’s bodies are assessed against men’s money. Bottle trains of champagne may seem irrational to a modern economist, but to an economic sociologist they are a type of ritual performance at the heart of hierarchical systems of prestige and masculine domination. Through highly scripted and gendered labors within the VIP space, the absurdity of extreme wealth becomes normal—even, with the right staging, celebrated and honorable.

I got into the scene because I could still pass for a “girl,” even though I was thirty-one when I met Santos, far older than the eighteen-to-twenty-five-year-old women that typically formed his entourage. I looked younger than my age and, as an ex-model, I could pass as pretty enough, though I was surely more stiff and sober and less desirable than the other girls—a fact that Santos sometimes reminded me of, like when he suggested I change out of my more manageable wedge sandals and into sexier heels.

There was another reason promoters like Santos let me follow them through the exclusive party scene. He was blown away by the idea that a professor, someone with a PhD who teaches at a university, was interested in learning from him. When I first met Santos, at a dinner in New York, I explained my project, telling him about my research on consumption, gender, and markets. He interrupted me in his fast, Colombian-accented speech: “What we do is psychologic. It’s psychological. Because you have to work people.” He went on to explain the stresses of the job, like when girls canceled on him with excuses to stay home moments before they were supposed to come out. The constant danger, he said, was that you could be left with no one at your party.

But Santos was also full of bravado, bragging about his status in this elite world.

“I’m the best. The very top. Ask anybody. Everywhere in the world, they know who I am, because you do the best party one time in one city, then everybody wants you at their party. They all know me.”

I came away from our meeting that night with the impression that he had been waiting for someone to study his world for a long time. As a mixed-race Latino from a poor family in Central America, Santos thought his own story of ascent among the global elite was remarkable, and he believed he was destined to be superrich like his clients. Shortly afterward, he showed me his roster of upcoming summer events and parties planned in Paris, Milan, Saint-Tropez, Cannes, and Ibiza. “They gonna fly me everywhere. It’s the top, top level. I go everywhere and it’s so nice.”

And so I joined him with three other women—to Santos, always, “my girls”—on a clubbing trip to Miami where we stayed together in the three-bedroom guesthouse of the Star Island villa. The cab driver at the airport told me it was the fanciest neighborhood in town, a place where the celebrities and moguls live. The guesthouse was probably very nice on most days, but on this weekend it was a mess from transient girls and days of party detritus. The rent was typically $70,000 a week for the villa, but the bankers were paying an inflated price due to the electronic music festival that weekend.

Hannah, a part-time model, part-time Abercrombie clerk, and part of Santos’s crew, looked shocked when she heard the bankers paid $50,000 to rent the villa just for the weekend: “Why? What’s the ±č´Çľ±˛ÔłŮ?”

The mortgage bankers didn’t have an articulate explanation. A group of four of them regularly came to Miami with their boss, George, the founder of the mortgage bank. We would see George and his colleagues at nearby tables at the clubs, where George told me the table rent cost them $30,000 a night.

“But I didn’t tell you that, you know, because I don’t want to be the guy that spills out what’s really going on.”

“$30,000? That’s a lot,” I said. “And what’s that buy you?”

“The best night of your life,” he said with a sarcastic laugh. “Okay, not really the best night of your life. It buys you some champagne and vodka.” That stuff is relatively cheap, as George knows, before the club adds its markup of 1,000 percent. But there is an experience to be had in these nights that George and his colleagues and Santos and his girls were all seeking.

“If you come, you gonna see,” said Santos, about this VIP world. Santos said this often in the days leading up to our trip to Miami. And when I arrived at the first destination in what would become an eighteen-month-long tour through the elite global party circuit, from New York to Miami, the Hamptons, and the French Riviera, I found an intricate gendered economy of beauty, status, and money that promoters like Santos pieced together night and day.

Now, ears ringing, I sat by the pool typing up my notes from last night, thinking about my own weird tangle of enjoying access to this exclusive world of the rich and the beautiful, while also being repulsed by it. The late orange sun dipped behind the palm trees. Soon, Santos and the rest of his girls would wake up, and it would be time to get ready to go out again.

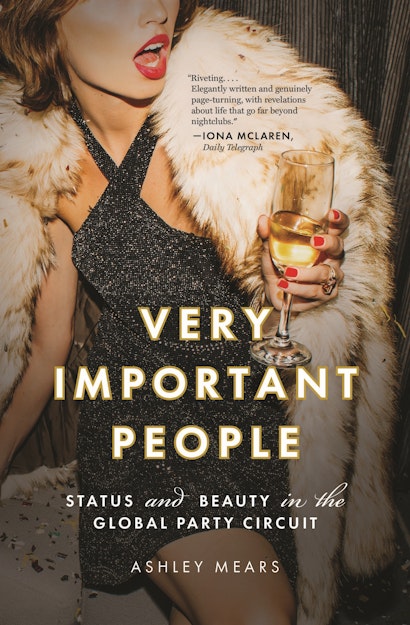

This is an excerpt from Very Important People: Status and Beauty in the Global Party Circuit by Ashley Mears.

av¸ŁŔűÉç the Author

Ashley Mears is associate professor in the Department of Sociology and in the Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Program at Boston University. She is the author of Pricing Beauty: The Making of a Fashion Model. Her writings have appeared in the New York Times, Elle, and other publications. She lives in Boston.