What really is a syllabus? Is it a tool or a manifesto? A machine or a plan? What are its limits? Its horizon? And who is it really for? And what would happen if you took the syllabus as seriously as you take the most serious forms of writing in your own discipline?

It’s so familiar. The first day, the first class meeting, the noises, the competing interests of choosing seats and choosing neighbors, the geometry of students and backpacks, tools, food, books. For you, it’s curtain up. You’ve brought with you a set of handouts, the ones you quickly say are also and always available online in the course learning module. You distribute the handouts, making eye contact as you do it—everyone is so young, and the class is more diverse each time you steal a glance. You’re looking for their response, even before they’ve read a word of what you’ve set down.

You remind yourself that your students are there for one of two reasons. Either they have to be there, or they want to be there. Either your course is a) required of everyone or maybe required in some specific track, or b) it’s an elective. You know that neither category guarantees an easy ride, and you wouldn’t want it any other way. Teaching is hard. One of your goals is to have the students who have to be there want to be there. Another goal is surely to make students who choose your course tell others that it was amazing, that you were terrific. Teaching is hard, you tell yourself again. Knowing that is part of being a teacher.

You feel the electricity of performance, the responsibility of winning students over to your discipline. You run through what you’re going to say this hour in a distracted, internal monologue. A few moments later, and the class has settled down into what looks like an attentive reading of the handout. It feels as if it’s your moment to lose: students poring over the little world you’ve created for them, a place where the hierarchy of the university—your mastery, their innocent but open-minded ignorance—is mediated by a simple document and the set of rules to which it conforms. Their eyes turn to you. Electronics are stowed. You pick up a piece of chalk. House lights down. You begin. You will be at that blackboard, chalk in hand, for sixteen weeks, and during that time your voice, and your brilliance, will fill the space.

You begin talking, but something strange is happening. All your expertise seems to have left you, and you’re jabbering on in what you recognize as a steady stream of amateurish nonsense. But that’s not the most horrifying part. What’s truly frightening is that the students are looking at you as if you’re making perfect sense—or, more accurately, as if it doesn’t matter whether you’re brilliant or banal.

Then the alarm clock goes off and you wake up. It’s four a.m., still dark, and you don’t have to be on campus for another two weeks. You spent last night fine-tuning your syllabus one last time and in the process ratcheting up your own anxiety.

You’ve just awakened from one version of the Academic’s Performance Dream. In the dream-class, you were about to tell the students something for sixteen weeks, which might be fine if your course were a one-way transmission to an adoring audience and nothing more. You wouldn’t really teach a class that way.

And yet you’re beginning to concede that the dream that woke you is more or less a critique—your critique—of your own teaching, your unconscious mind accusing you of a particular kind of earnest, hardworking—what to call it?—laziness. You’re half-awake now and recognize too much of your own teaching style. It isn’t a horror show—far from it. Reasonably genial, largely inert, a series of solos in which you enacted knowledge of the subject, underscoring memorable points with chalk, points dutifully copied by a silent room of students whose own thoughts remained locked away for the semester or at least until the final exam.

The sun’s coming up, and your morning resolution is not to teach that way again. You’re not even sure what kind of teaching that was, but it felt deeply incomplete. You’re awake now and, breaking the rules you’ve set for yourself, you’ve got your laptop open in bed. You’re anxiously looking over that syllabus one more time. Is it too much, too little, too complicated, too filled with arrows that point the student to side roads? Could you read your own syllabus and make a reasonable guess as to what the course wants to accomplish, as opposed to what your department’s course catalogue says that the course studies or describes? Could you recognize what the course challenges students to do? And how exactly would you, the teacher who wrote that syllabus, follow through on your own expectations for students?

Dreaming or waking, these questions never seem to go away. Teachers aim high. Big targets, big goals. A class that sings with intellectual engagement. Rigorous but fair grading, and each student doing better than you had hoped. The gratification of giving the exemplary lecture to a room of attentive students. Your own delight in the difficulty that comes with thinking seriously about things that count. All good goals, which, taken together, add up to an ideal of the teacher-focused class. “You’re a star!” says somebody in the hallway, possibly without irony.

But stars are bright, distant things, and the light they throw off is old, old news. What might it mean to teach now, to shine now, in the present, close to the moment and our students? This question is about more than diversity or age or ethnic sensitivity or a sympathetic engagement with the complexities of gender, or disability, or any of the other qualities that distinguish person from person. First or last, teaching is inevitably about all of these things.3 But to be present asks that we do so much more. Our students, hungry for something that starry light can’t provide by itself, need from us not just knowledge—even knowledge tempered by sensitivity—but craft.

The myth of Prometheus—the Greek name means “forethought”—tells us that this most generous of Titans stole fire from the gods and brought it to us clay-built human creatures, functionally kindling life in our dark world. Teaching in the present is a bit like stealing fire. Here, o starry teacher, the fire is your own but briefly. Teaching is renouncing the glamour and assurance of the well-executed solo and sharing that light with your students, moving the focus from something we’ve long called teaching and giving the torch to learning. You can teach by yourself, or at least tell yourself that you can, but you can’t learn (let’s for a moment allow it to be a transitive verb meaning “to make them learn”) by yourself.

Modern English learn has as one of its antecedents the Old English form gelaeran, which meant “to teach.” This etymological paradox isn’t a paradox at all, of course. If teaching is the thing that happens when students are learning, subject and object come to be bound together, like Aristophanes’s conception of the sexes balled up inseparably in The Symposium, a Möbius-like continuum of teaching and learning, enacted by teacher and student.

We begin to discern the contours of this perplexing space of learning when we awake from the dream (it was always only a dream, never a solid reality) of the masterful teacher delivering knowledge. We can map out something so complex only by making a concerted effort to describe its nuances, conundrums, its areas of density and lightness. We perform this mapping and engage in this forethought when we compose a syllabus, but only if it is indeed an attempt to map the space of learning. Which means that, as we’ll say in several ways throughout this book, a syllabus isn’t so much about what you will do. It’s about what your students will do.

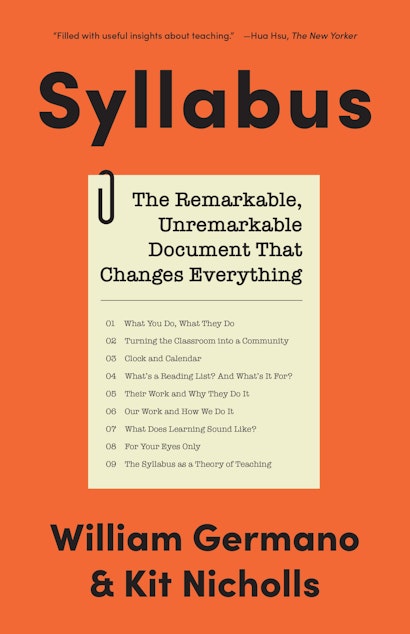

This essay is an excerpt from Syllabus: The Remarkable, Unremarkable Document That Changes Everything by William Germano and Kit Nicholls.

William Germano is professor of English at Cooper Union. His books include Getting It Published and From Dissertation to Book. Twitter @WmGermano Kit Nicholls is director of the Center for Writing at Cooper Union, where he teaches writing, literature, and cultural studies.